Geertje Brandenburg is a Dutch artist who works with a tender, introspective precision, exploring how identity is shaped by the stories and silences passed down through her family. Her work moves between the raw and the delicate, tracing the quiet mysteries that linger in names, objects, and remembered places.

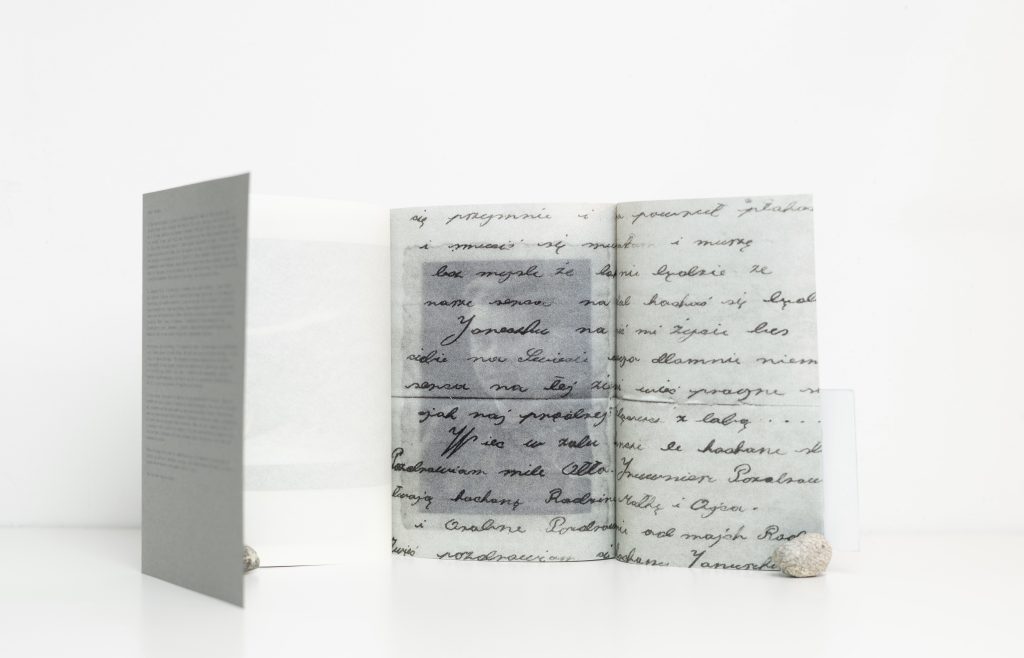

Her book Summerhouse began with the discovery of letters her grandfather wrote about his time as a forced labourer in Germany from 1943 until 1945. As she read them, she felt their memories echo inside her own — wondering what parts of him live on in her, and how the past continues to shape the present. Summerhouse becomes a place where inherited stories are reopened, examined, and gently transformed — allowing both healing and new meaning to emerge.

Can you tell us a bit about your background, artistic practice, and how your interest in identity and family history began?

As someone who was named after my grandmothers, I’ve never had a name that was just my own. This always fascinated me. I come from a family who, as my aunt once said, “received the curse of keeping.” I’m constantly reminded of this inheritance — not just through my name, but also through the objects that surround me. Most things in my life are not mine in the first place: a chair from a distant great-aunt, the cutlery of my grandparents’ parents, small things passed down and held onto.

This idea of carrying names, stories, and objects that precede me has become a recurring theme in my work. It blurs the lines between people, generations, and things. In my artistic practice, I often ask myself — and others — whether we can recognise ourselves in a photograph of our grandmother, or in a note left behind by a stranger on the street. Is identity a sum of parts?

Summerhouse is a deeply personal and introspective work. How did the project take shape from its first idea to its final form?

I think the story was so personal that it took me a long time to find the right form for it — a way to tell it intimately without it becoming a classic war story. Summerhouse had been floating around in my mind for years before I finally began the work in 2021. My fascination with identity was always tied to my grandfather, who was a very idiosyncratic person. His peculiarities seemed to be rooted in something from his past that he never talked about. When I first read the letters he wrote — which eventually became the foundation of Summerhouse — I immediately felt that I had to do something with them. But I couldn’t shape it into a project yet; it needed time to simmer in the back of my mind for a year or two before I was ready to start the research.

In 2020, I graduated with a BA in Fine Arts at the HKU and received the Keep an Eye Photography stipend for my graduation work Medusa. That moment really jumpstarted Summerhouse — suddenly I had the means to embark on a larger research project. While working on it, the project took many different forms. At first it was a clear, linear narrative. Then it became more of a research-driven process that slowly transformed into a series of artworks. These works were shown in several exhibitions — unfortunately without visitors because of Covid in 2021. Eventually, the project found its final form as a book.

How did it feel to spend time in Germany while working on the project? Did being in the same place as your grandfather change your perspective on his life or your work?

It felt incredibly strange to go to Germany and search for the direction this project would take. It was January 2021, and the Covid restrictions were still very strict. I found myself walking through what felt like an abandoned place. Because I wasn’t allowed to enter most buildings, I spent my days outside — in graveyards, in forests filled with abandoned buildings, — trying to imagine the paths my grandfather might have walked and the buildings he might have seen, trying to understand where our stories meet.

At some point I did the math and realised that I was the same age then as he had been in 1943, when he was forced to come to this place. Recognising that parallel — seeing where I stood in my own life, and catching a glimpse of what his life must have been during the war — really put everything into perspective for me.

What was the most surprising or moving thing you found during your research?

I travelled to the east of Germany hoping to find a way to capture this story. I wanted to walk the same streets my grandfather walked, touch the buildings he touched, and look for some missing puzzle piece — something that might answer a question I had about myself.

Originally, I imagined Summerhouse as a collection of facts, a kind of documentary work that could bridge generations. But once I arrived, I realised that the beauty of this project wasn’t in the answers it might provide, but in the questions it asked. While I was there, I learned to surrender to the beauty of the unknown. In a way, I think I went to Germany trying to be a journalist — and instead, I found myself becoming a poet. That shift has shaped how I think about my work even now.

“In a way, I think I went to Germany trying to be a journalist — and instead, I found myself becoming a poet. That shift has shaped how I think about my work even now.”

Collage seems to be a central technique in your work — what draws you to it?

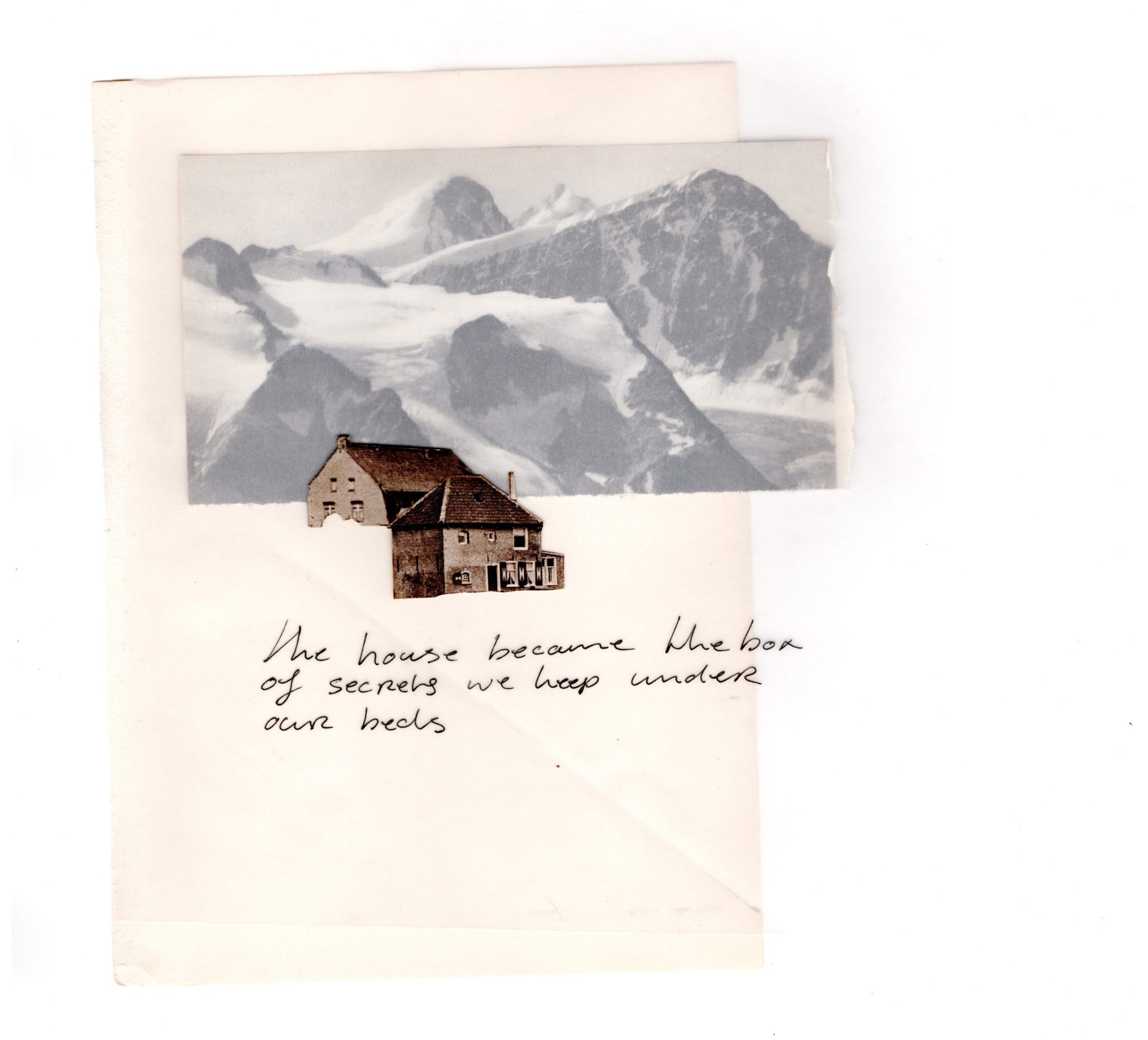

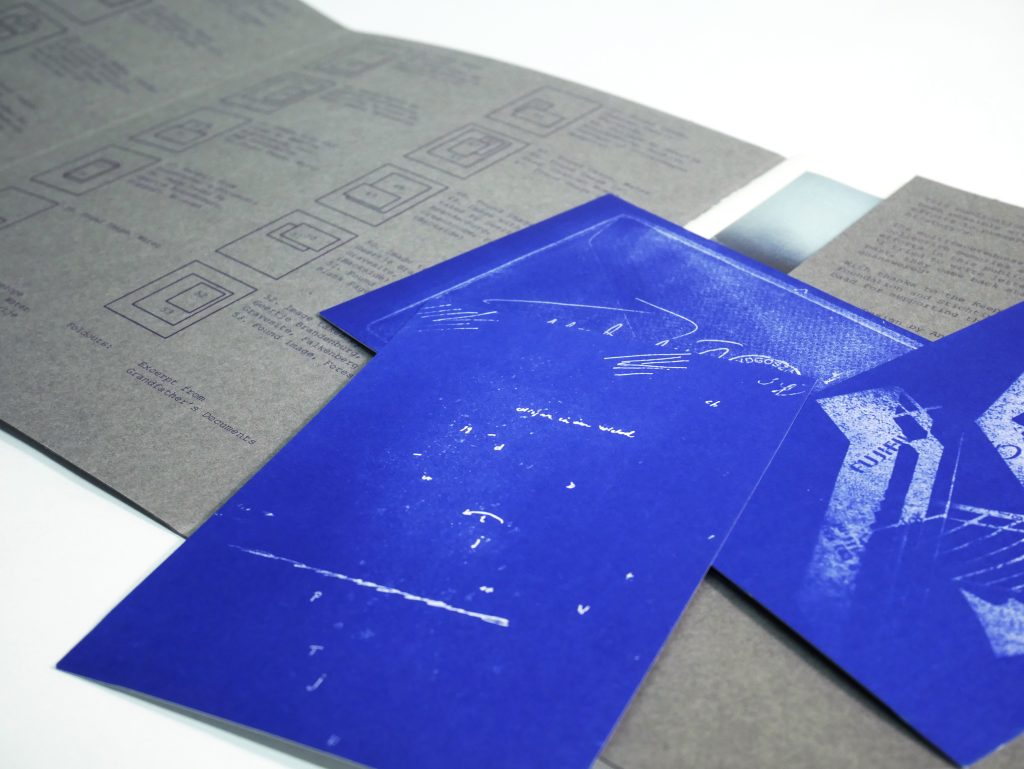

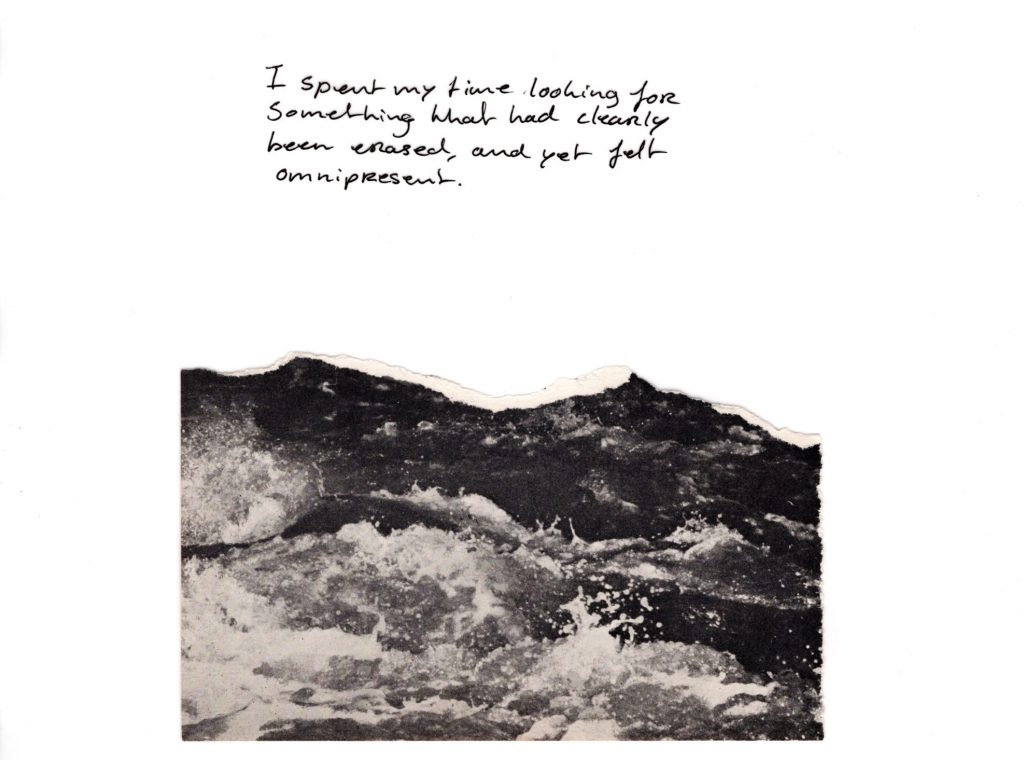

Collage attracts me because it allows everything to exist at the same place at once, without needing to blend or resolve the edges. I can take an image torn from a 100-year-old book and place it next to a photograph I made yesterday — and somehow these moments, far apart in time, become one. The personal image merges with the impersonal page; together they become more than the sum of their parts. This is also where the poetry enters the book. Documentary material sits alongside historical imagery, and even images that have no direct relation to the story evoke a feeling that belongs to the project. Different temporalities, truths, and sensitivities can coexist within a single frame.

I did extensive historical research for Summerhouse, hoping it might become a kind of documentary work. But the material reality of the research could never exist on its own alongside the emotional complexity of a story that spans generations of feelings, myths, and fantasies. Collage became a way to bring these different voices together without needing to explain each one explicitly. By cutting a shape out of one image, you open a portal to the next — another story, thought, or fact. Each image meets the next along its edges; they cannot exist without each other, just like the intertwined stories that Summerhouse tells.

How did you approach the process of turning Summerhouse into a book, and what were some of the challenges or discoveries you made?

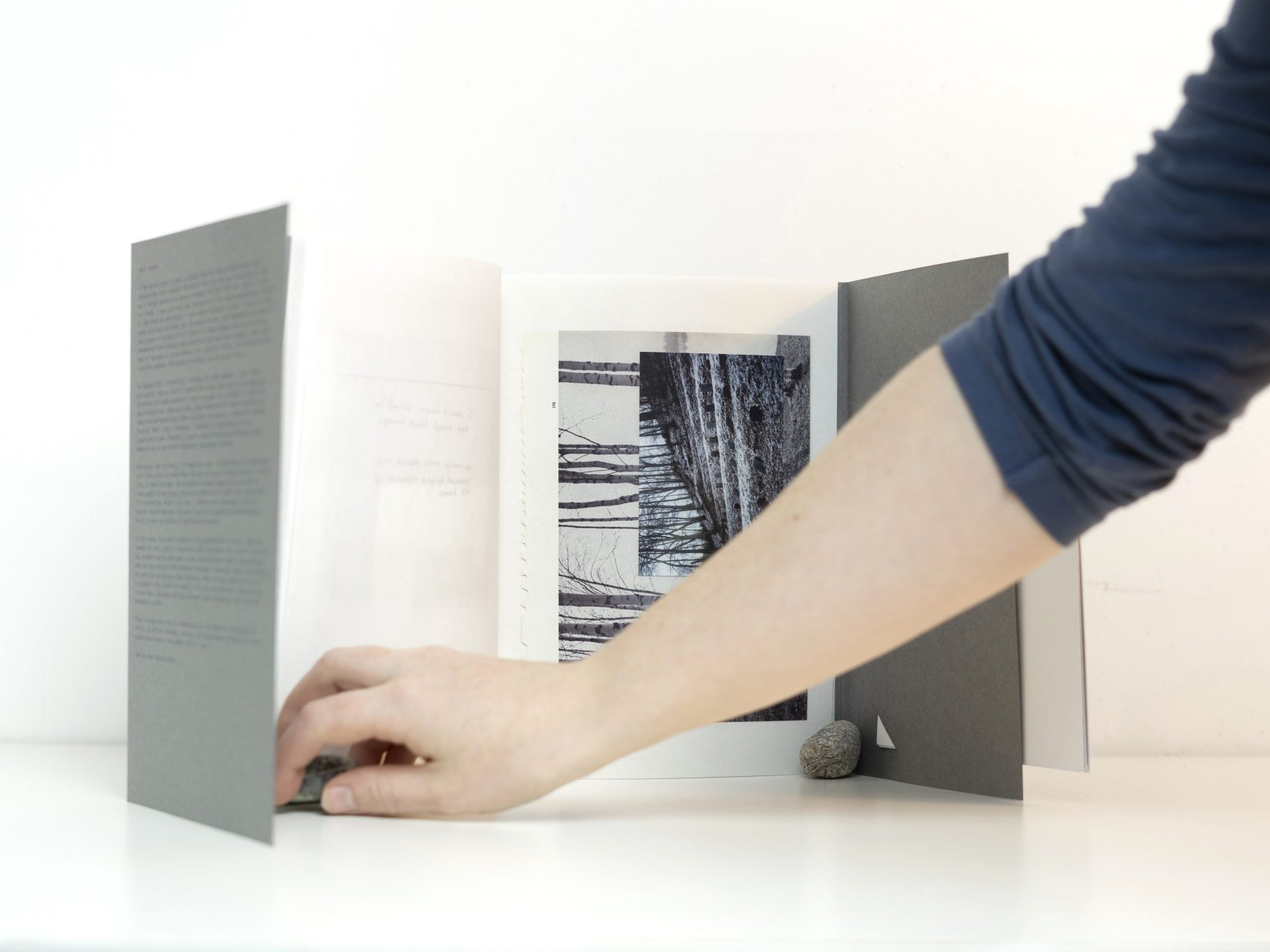

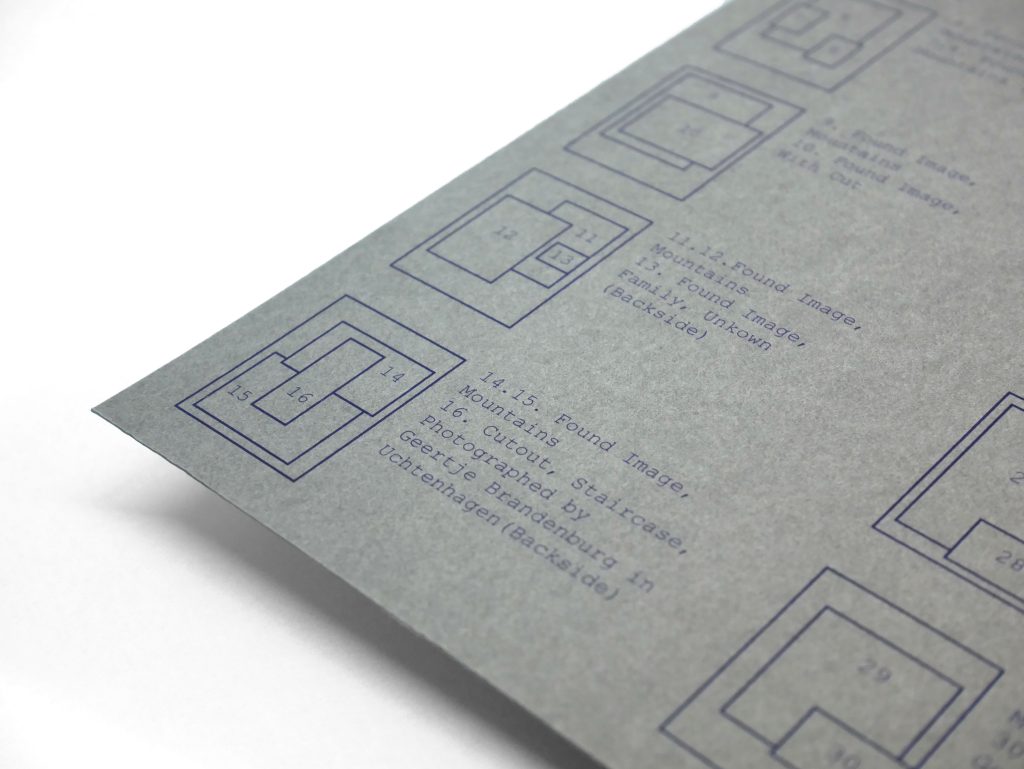

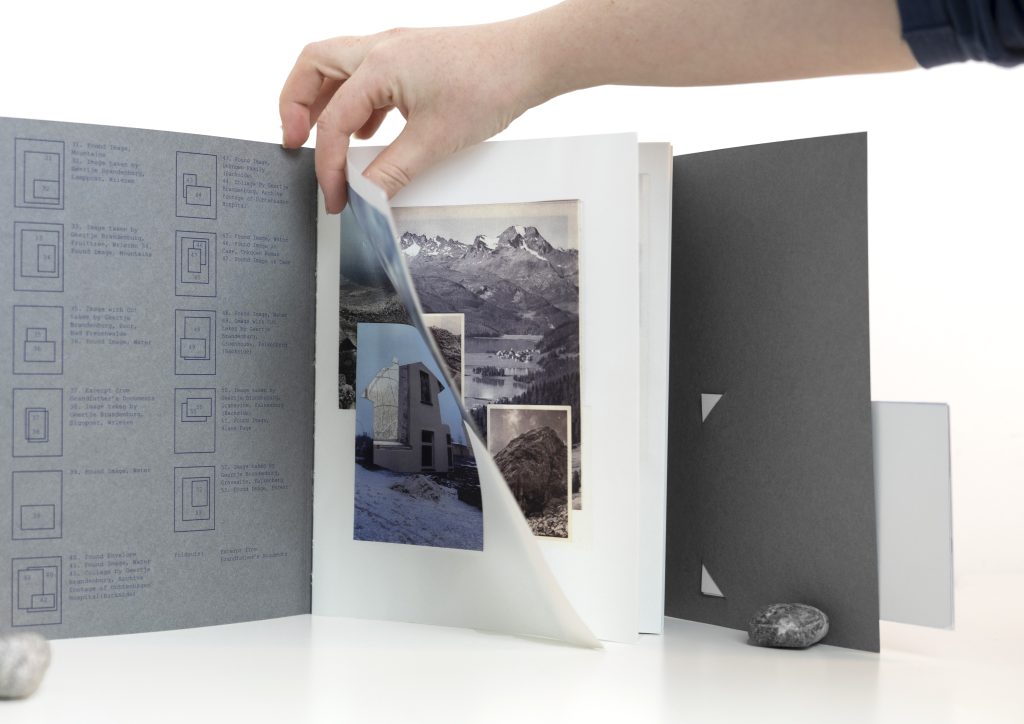

Turning Summerhouse into a book was quite a challenge, because the project originally existed as a series of works meant for gallery spaces. The first big step was finding a graphic designer who could understand the subtlety and intimacy of the story. Eventually I began working with Andreea Peterfi, who became my main collaborator on the book. We met in each other’s homes, surrounded by boxes and folders filled with images, prints, and fragments. I would lay everything out and share the stories behind the materials. Working in this very physical and intimate way ended up shaping the entire form of the book. We wanted it to feel like opening a box of secrets — images overlapping, shining through semi-translucent pages, revealing and hiding at the same time. Together, these layers create a story full of textures and questions, rather than clear, singular answers.

Throughout the process of the project, I also learned a great deal about myself as an artist. Because it was my first major project after graduating, it made me realise how drawn I am to showing questions rather than answers — and that understanding has shaped my practice in many ways. It was also the first time I fully embraced the personal as a legitimate starting point for a work. Through exhibiting Summerhouse and speaking with others about it, I realised that sharing something personal can create space for others to reflect on their own memories and stories. In that way, the work becomes a conversation rather than a statement.

Are you currently working on any new projects that you can tell us about?

I’m currently working on a project that looks at the similarities between religious and medical rituals. Many religious rituals actually began as medical practices, and many medical rituals we still follow today come more from a place of hope than from scientific understanding.

As with all my projects, it started with an initial point of fascination. I research, collect references, and slowly the material begins to shape itself into a piece of fiction. I write short stories and poems alongside the visual work, and these texts often form the basis for where a project wants to go. This new work is beginning to form around the idea of a person without a shadow. Traditionally, a shadow is linked to a person’s “dark side,” so the absence of one suggests a kind of un-humanness — a being in transition, between realms, moving through spaces that the rest of us cannot reach. I keep asking myself: where does this person exist, and what conditions cause them to become shadowless?

The project is still very much in its early stages, so I’m experimenting — reading, researching, writing, and playing with different materials in the studio. It’s often the most frustrating phase, because you can sense something is there but don’t yet know its form. But it’s also the most exciting, because the work feels completely open, waiting to reveal itself.

Photo by Marcelle Bradbeer

Photo by Marcelle Bradbeer

You have just returned from a residency in Iceland. What was your experience like and how did it help you with your new project?

Iceland was an incredible experience. I stayed in Stöðvarfjörður, a town of about 200 people, completely isolated from the rest of the world. Once a week I would drive an hour to the nearest town to get groceries and basic supplies. That isolation created a very intense sense of focus — all you can really do there is work and think.

Being so removed from everything was also perfect for the project I’m developing. I researched medicinal herbs that only grow in Iceland, looked for crystals in the mountains, and turned to old sagas and myths to study religious rituals. I knew I couldn’t bring the entire work back home with me, so instead of creating something permanent, I made an ephemeral intervention in the landscape where the work was created — a gate sewn from tracing paper. It clearly doesn’t belong there, and yet it somehow merges with the environment. It’s funny, because I’ve always been strict about not using sewing in my work; I wanted to keep at least one hobby free from my practice. But after my initial plans didn’t work out — and with materials being so difficult to access — I shifted direction. Before I knew it, the sound of tracing paper crinkling through the sewing machine became the soundtrack of my time in Stöðvarfjörður. I’m very grateful for that isolated moment in my practice, sitting behind the sewing machine and letting the work unfold in its own way.

![Geertje Brandenburg -Fish Factroy [photo credit Marcelle Bradbeer]](http://blog.sproutpublish.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Geertje-Brandenburg_Fish-Factroy_web_01photo-credit-Marcelle-Bradbeer-1024x683.jpg) Fish Factory – Photo by Marcelle Bradbeer

Fish Factory – Photo by Marcelle Bradbeer

You have an upcoming exhibition in Utrecht — what can we expect to see there?

The upcoming duo show with Faria van Creij-Callender explores what identity means to each of us. The exhibition is titled tussen twee oevers (“between two riverbanks”), which points to ideas of duality, but also of transition — standing on one bank and looking toward the other, separated yet connected by the river that belongs to both of us. Faria and I share a fascination with the pluriformity of identity. Our personal stories become works of fiction, drifting between riverbanks of different truths and realities.

Tussen twee oevers opens at Kunsthal Kloof in Utrecht on Friday, November 21st at 20:00, and will be on view until December 21st.

Portrait of Geertje Brandenburg in her studio.

Portrait of Geertje Brandenburg in her studio.